Deep Calling Unto Deep: A Contemporary Guide to Orthodox Spirituality (Part Two)

Watchfulness and Warts

Just as a child, young and guileless, delights in seeing a conjuror and in his innocence follows him about, so our soul, simple and good… delights in the delusive provocations of the devil. Once deceived it pursues something sinister as though it were good… In this way its thoughts become entwined in the fantasy provoked by the devil. Then, seeking to contrive some means through which it can actually attain what attracts it, the soul assents to the provocation and, to its own condemnation, turns this unlawful mental fantasy into a concrete, action by means of the body.

—St. Hesychios the Priest

At the end of Part 1, we recognized something critical that always seems to elude us—that beneath our immediate sense of self, which automatically identifies with the endless stream of thoughts, feelings, and desires flowing through our consciousness, lies a deeper, steadier self. This deeper self is not defined by the transient mental dramas emerging from these thoughts, feelings, and desires but rather by its capacity to “step back,” realizing it's seated in the audience and can calmly observe these dramas like a movie playing on a big screen. Gregory of Nyssa describes this deeper, steadier self as ineffable—an image of divine unknowability itself.

Yet, while becoming aware of this deeper, ineffable self in theory is revelatory, consistently inhabiting this self in practice demands something more. It requires us to clearly recognize the carousel of thoughts, images, and desires constantly flowing through our minds for what they truly are. To do this, we must first understand the difference between complex thoughts and simple thoughts and then identify the mechanism by which we habitually identify with them.

A simple thought is simply an image arising in the mind without any particularly powerful feeling or desire attached to it. For example, when you recall a conversation you had with someone yesterday or when you remember you have made plans with friends after work. Simple thoughts appear without much intensity or drama, passing naturally through consciousness without compelling us to linger upon or inhabit them beyond what is necessary.

A complex thought, however, is an image that arrives coupled with a powerful impulse or emotional charge, inclining us to engage with the image or object the image represents in an unhealthy manner. It presents itself as a scene in an ongoing drama we must participate in, or as one we can participate in by actualizing a future self who has a better job, or sexier wife, or a better look that will get them more attention. It also could be a memory or need to relive a past failure and occupy a drama filled with toxic shame. Such complex thoughts carry the strong gravitational pull that disposes us toward identification with something foreign to us—something not truly reflective of who we really are.

For instance, recall the exercise we called the “mental theater.” When you closed your eyes and calmly observed the scenes unfolding on your internal screen, you quickly discovered just how powerfully these “complex thoughts” could grip your sense of identity. Whether picturing personal triumph or painful embarrassment, you instinctively entered each scenario as though it were actually happening to you in the present moment.

In that unconscious instant, a critical transition took place: you moved from being an observer to becoming a participant in these passing dramas. You shifted in a flash from being seated safely in the audience to “suspending your disbelief” and joining the actors on screen.

This is the difference between the steady, watchful self—a self aware that it is seated in the audience—and the imagined self, who lives in the narrative unfolding on screen. The first is able to stand guard over one’s heart and not grant these dramas or demanding thoughts attention, the latter becomes a passive object manipulated by every thought, desire, and drama that comes one’s way.

To break free from this cycle, we must clearly understand how these initial impulses or dramas—what the Eastern Christian tradition calls logismoi—go from merely appearing on the screen of our awareness to taking root deep within our hearts as passions. To illuminate this process, consider an analogy: a wart.

Warts

At first glance, a wart appears as an integral part of your body, inseparable from your skin. Yet the wart is not genuinely you—it’s caused by a virus, a foreign invader that infiltrates and hijacks healthy cells, creating something unnatural and distorted. Although initially appearing inseparable from you, with proper care the wart disappears, leaving the healthy skin intact and revealing clearly that the wart was never truly part of you—it was an unhealthy growth temporarily attached.

In a similar way, our minds are constantly infiltrated by what the Eastern Christian tradition calls logismoi: complex intrusive thoughts that appear spontaneously and subtly present themselves to us as deeply personal. Unlike simple fleeting thoughts, logismoi typically arrive already attached to powerful impulses—to incline or dispose ourselves in certain ways. They appear as vivid narratives we feel compelled to occupy, images we feel irresistibly drawn toward or repulsed by, or painful memories triggering profound shame or self-loathing.

When a logismoi first emerges, we might imagine an idealized scenario: receiving a promotion, relating to another person in a novel way, receiving praise—and instantly feel a deep longing, believing that our happiness or identity is dependent on it. Or we might recall a past humiliation and feel immediate shame, becoming convinced this shame is integral to who we truly are. At these moments, the logismoi is merely a visitor in our awareness, not yet rooted in us. Yet if we don’t “step back” from it immediately to let it pass but begin to entertain it, letting ourselves “suspend our disbelief” and enter into the drama, we will always come to identify with it, mistakenly believing it genuinely expresses something fundamental about ourselves. We will assume these powerful impulses and desires represent our true self and must be acted upon.

This crucial mistake—identifying ourselves fully with these intrusive thoughts and impulses—is how logismoibecome deeply embedded within us. Much like a wart virus quietly infiltrating healthy skin cells, the more we entertain and emotionally engage these logismoi, the more deeply they become rooted, transitioning from passing mental phenomena into powerful emotional habits activated within our heart—the spiritual core of our being.

Once activated in our hearts, these impulses become persistent, deeply entrenched emotional habits, what the ancient spiritual tradition calls passions. Passions are not merely strong emotions; they are habitual emotional dispositions formed from repeated identification with these complex internal narratives and images. Anxiety, envy, anger, despair—all these passions arise precisely from repeatedly believing that the transient impulses and desires triggered by logismoigenuinely define who we are and what we must pursue to find fulfillment.

Yet just as a wart is not truly part of our body, passions are not genuinely part of us. Beneath their turmoil lies our true identity—an ineffable, stable self, created in the image of God. Our deeper self remains quietly awaiting our return.

The essential practice to reclaim our genuine freedom is precisely what the ancient tradition calls watchfulness. Watchfulness enables us to recognize logismoi clearly at the very moment they arise, to observe without immediately identifying with the impulses they provoke. When coupled with prayer, it allows us to gradually uproot passions already embedded within the heart. Through this process, we rediscover our agency, realizing that we have the freedom not to indulge every impulse or desire and gain the ability to reconnect with our deeper self.

Precisely how we begin to cultivate watchfulness so that we can identify logismoi clearly and uproot our spiritual warts is where we now turn. First, I will offer an illuminating example from my own experience—a powerful dream that expanded my sense of what was possible and reconfigured my entire perception of the nature of thought itself. Afterward, we will move toward concrete examples of how to practically apply this practice to our lives.

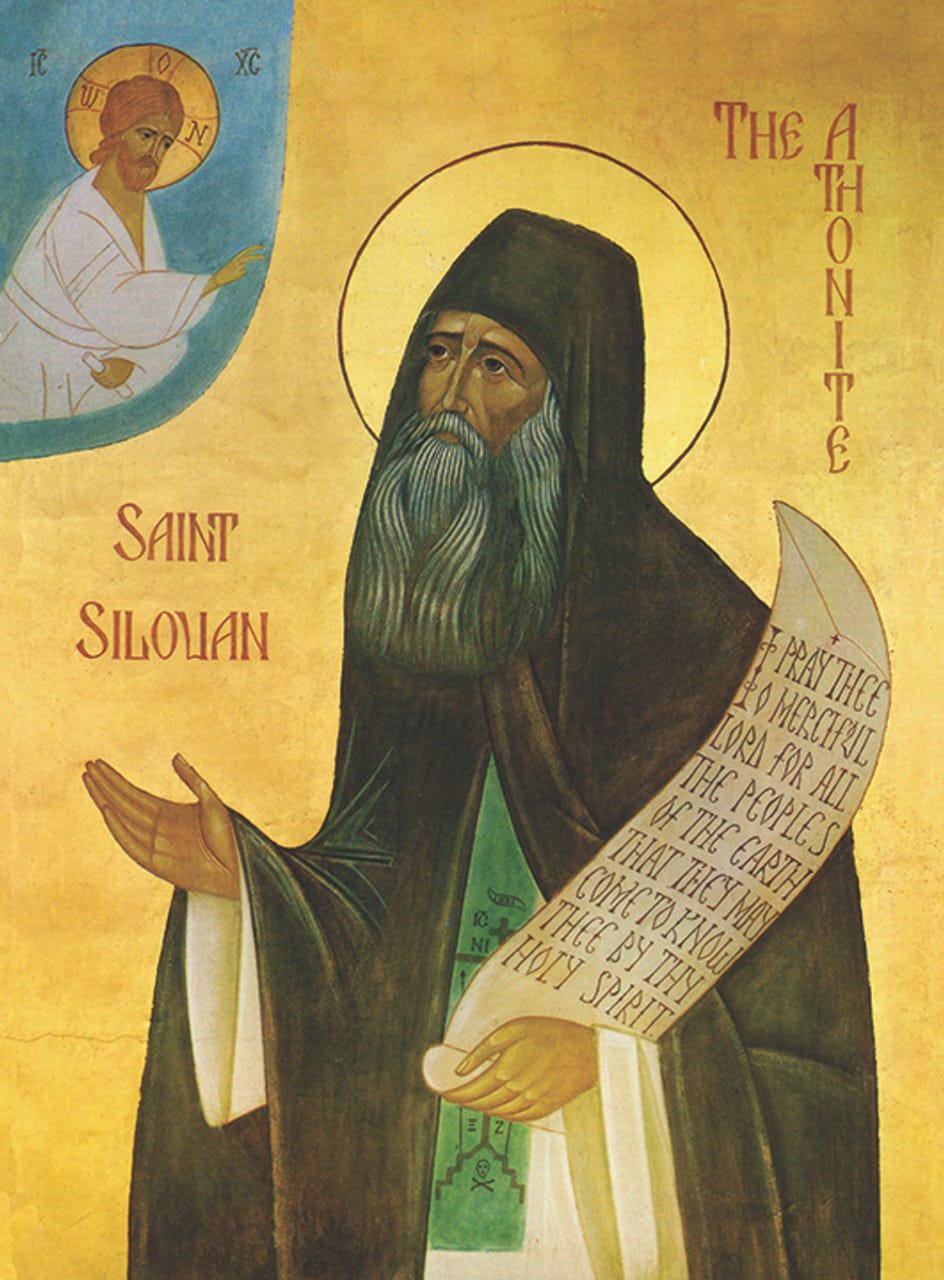

A Visit from St. Silouan the Athonite

One night, several years ago now, I had a powerful dream which has left a permanent mark on my life and perception of everything.

In this dream, I initially found myself overwhelmed by a flurry of thoughts, each fighting over my heart, inclining me toward anxiety and then lust and then hate and then despair. There seemed to be no end to the thoughts and each had such possession of my heart that I couldn't see where the thought ended and I began.

Then, suddenly I saw St. Silouan standing next to me. He placed his hand gently on my head, and a calming, immaculate warmth washed over my mind with a flash of pure, white light. Instantly, something shifted—I was no longer my thoughts but clearly saw each thought as something external, like a virus seeking to implant itself in my heart.

I looked at him, and as if reading my mind, he calmly instructed me: “Here is a thought.” Sure enough, a thought immediately arose, grasping at my attention, striving to embed itself in my heart—and as soon as it appeared, he gently said, “Now let it pass.”

Again, a thought came, and again he instructed, “Let it pass.”

His dew-like words revealed to me a truth that has remained with me ever since: there would never be a moment when I could finally cease stepping back and letting thoughts pass. There would always be another thought, another impulse requiring the same gentle vigilance.

Yet, this realization wasn’t discouraging. Instead, it illuminated the path ahead and most importantly, impressed upon me irrevocably that I was not my thoughts, and the logismois came from somewhere else.

Practical Application

Just as in my dream, where St. Silouan guided me to calmly and patiently recognize each thought—“Here is a thought; now let it pass”—we too can take intentional moments each day to step away from our automatic identification with internal dramas and impulses, consciously noting and then releasing each logismois as it seeks entry into our hearts.

A helpful way to establish this practice is to set aside brief, intentional periods of quiet each day—perhaps just five or ten minutes—to sit in stillness, simply observing the carousel of thoughts and feelings as they present themselves. During these moments, you might softly acknowledge to yourself the nature of each impulse as it appears—"Here is a thought of anxiety," "Here is a memory of hurt," "Here is a desire for approval"—and then allow each one to pass quietly without judgment, without following where it seeks to lead.

Over time, this simple yet profound practice strengthens your capacity for watchfulness, gradually weakening your habitual identification with passing thoughts and desires. Just as consistently applying treatment to a wart weakens and eventually removes it, consistent watchfulness steadily diminishes the power these logismoi hold over your heart, helping you reconnect more consistently and effortlessly with your deeper, steadier self.

Yet, this practice is just the beginning. In the next post, we will deepen this practice by exploring the complementary role of prayer—specifically, the ancient Orthodox practice of descending the mind into the heart. By coupling watchfulness with prayer, we will learn to invite the fiery, transformative presence of God into the depths of our being. In this descent, divine grace will begin to burn away the spiritual warts of our deeply entrenched passions, illuminating a path that leads us beyond merely observing our thoughts, toward encountering the radiant ocean of God's presence within us—where we might eventually come to know God as He knows us.

Thanks for sharing your dream about St. Silouan. He has had a profound impact on me as well- particularly the words he received from the Lord: "Keep your mind in hell and despair not." It's a relief to recognize that the thoughts won't stop- but that with Christ there can be a restfulness even in the midst of them.

Almost 33 years ago I came into Orthodoxy out of a new age school of self awareness. I came for the spiritual depth. Immediately I found no use for any other spirituality. I was given two prayers. As I prayed those prayers more prayers came until I had written a 500 page book of prayers. As I prayed those prayers, more prayers came. I have written a series books of prayers called An Arrangement of Prayers Toward Theosis. Every day I share a ten prayer section from these books on substack.