No matter how ‘right’ you may be on various points, the most important thing is not ‘rightness’ at all, but Christian love and harmony. Most ‘crazy converts’ have been ‘right' in their criticisms, but they were lacking in Christian love and charity and so went off the deep end, alone in their self-righteousness. Don’t you follow them!

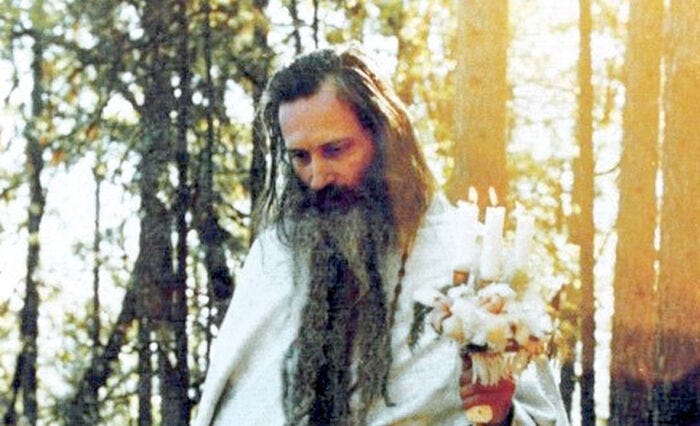

+ Father Seraphim Rose

Whenever the name of Fr. Seraphim Rose comes up, it’s bound to spark controversy. To some, he is the first American-born saint. To others, he is nothing more than an extreme ascetic—defending six-day creation and the long-abandoned doctrine of the toll houses. In short, it’s easy to dismiss him as a fanatic and leave it at that.

But to begin with the controversy is to miss the man.

Before he was Fr. Seraphim, he was Eugene Rose—a young man incapable of fitting into the cookie-cutter life laid out for him by his parents. Though born into affluence in San Diego and raised in a Methodist household, nothing could satisfy his hunger for something deeper and intellectually demanding. And so, before long, he declared himself an atheist.

Yet atheism was never enough. His rejection of Christianity only sharpened his hunger for something more than the shallow culture he had fled. He devoured philosophy and religion, searching for a tradition that could bear the weight of ultimate questions. For a time he fell under the spell of Alan Watts, whose popularizations of Eastern mysticism suggested there might be depths beyond the thin rationalism he had left behind. But it did not take long before he saw Watts for what he was—a charlatan—and he moved on, continuing his studies at Berkeley.

It was there that the first truly life-changing encounter came, when he met the Taoist teacher Gi-ming Chen. Having recently read René Guénon and been convinced that the truth of any religion lay in the continuity of its tradition, Rose recognized in Chen the real thing. Chen embodied Taoism—someone who not only taught, but truly lived what he believed.

Rose’s brilliance and gift for languages made him a natural candidate for an academic career, and he entered a master’s program at Berkeley. Yet what absorbed him most was a massive book he had begun to write—an ambitious genealogy of American nihilism. Page after page, he traced what he saw as the philosophical collapse of the modern world. But the deeper he went, the more the project consumed him. Drinking, coming out as gay, and endless rebellion—none of it brought relief. The pages piled up, but so did the emptiness. His mood hovered just above suicidal. Every path he tried—academic, philosophical, spiritual—promised depth, yet all circled back to the same futility, the same void.

What finally saved him was not the completion of his monumental tome, nor the promise of an academic career, but a chance encounter with an Orthodox church. At first, he simply slipped into services, curious but detached. Yet over time he found himself unable to ignore what he experienced there. The beauty, the depth, the quiet sense of truth pressed in on him. Even while still living as a homosexual, the conviction grew stronger: here, at last, was the answer to his agony. Eventually, he ended his relationship and chose to surrender.

He gave himself to Orthodoxy completely—not merely to its doctrines or worldview (though he accepted both), but to its way of life. He prayed. He fasted. He learned obedience. He left behind his unfinished book, which would have told the world everything wrong with it, and abandoned his academic ambitions. Instead, he allowed himself to be carried by the life of the Church.

In time, he and a friend founded a monastery. And by all accounts he put his old self behind him and entered into an entirely new life. There, perhaps for the first time, he began to know happiness—a happiness few are ever granted.

Of course, some still balk at the books he published in his early years of monasticism. But to focus on those writings is to miss the larger point. Having once needed to know everything, to prove himself a scholar, he laid down even the pretense of intellectual supremacy for something far greater: a spirit of peace.

Anyone who has listened to his later lectures will know this. By then, the voice of controversy had vanished. What you hear instead is its opposite: a man gently trying to steady his fellow monastics from one extreme or another. He speaks with clarity and practical wisdom, never needing to prove anything. Some of the ideas he had written as a younger monastic may indeed have been specious. But in the end, what does it matter, when he had found his way into Life itself?

As time goes on, I find myself more and more inclined to admire Fr. Seraphim. Not for what he wrote, but for the life he lived and how that life came about. He was able to let go of what Addison Hodges Hart has rightly called “intellectualism” and find peace in simple obedience.

Like Rose, I spent time in graduate school studying philosophy of religion. Like Rose, I too spent years in despair, and even after those years, fought to understand the underlying structures and genealogy of our modern world. And even after becoming Orthodox I have continued in my studies to gain a passable knowledge of metaphysics and a strong knowledge of the Fathers. But in the end, when I look at Rose’s life and I look at mine, I wonder who really had a better grasp of it. I—who have gained an increasing inability to approach the Liturgy? Or the one who may not have always been technically right, but gained hold of the Way, the Truth, and the Life? The one who now stands at an arm’s length from what was once an ever-deepening mystery? Or the one who acquired a spirit of peace?

I can’t help but wonder if it wouldn’t be better if I myself were willing to allow myself to accept a few pious fictions, if it meant no longer standing at a distance, but entering into the Mystery of Life itself.

"I can’t help but wonder if it wouldn’t be better if I myself were willing to allow myself to accept a few pious fictions, if it meant no longer standing at a distance, but entering into the Mystery of Life itself."

I made the decision to do this with the traditional stories about the Theotokos. I finally decided, after being in the Church for 10 years, to just accept what the Church was teaching me about her as "true," even though every cell in my brain was saying, "Yeah, right..." in utter disbelief. Then I decided to pray an akathist to her for 40 days for a friend who was ill, and at the end of the fulfillment of this process, something inside me had changed. My mind stopped resisting and pushing against the stories about her and simply accepted them, and she also became much more real to me. It was an experience that cannot be explained logically; rather, it was a transformation of my heart - but I had to make the first move and take the first step towards her. And while my friend was not healed physically, but a few years later he was baptized into the Orthodox Church which - if you knew him - was an absolute miracle!

Saint Anthony's Monastery in Arizona published a huge tome collection of patristic writings which they say supports the toll house theory, so I don't think it has been totally rejected.