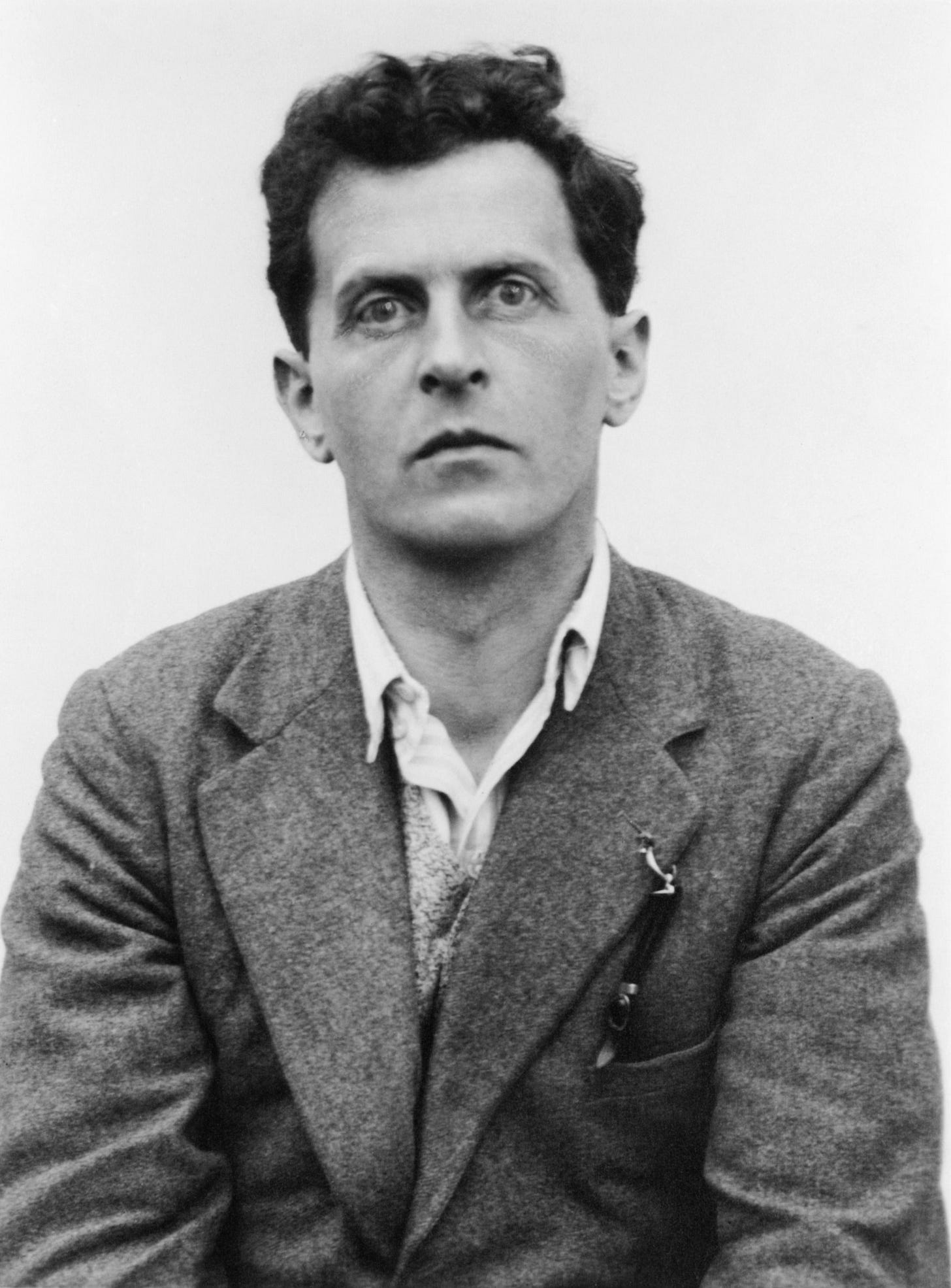

Wittgenstein, 1929

Most photos taken by professionals speak more about the period of time they were taken in than of the person being photographed. This is not so with Wittgenstein. He leaps out of the frame, his eyes alight with intensity—his gaze weighing heavily on the viewer, even though it’s not the viewer (or the camera) he’s looking at. His vision somehow extends beyond the frame. Indeed, his gaze seems to extend beyond the limits of the frame and, perhaps, beyond the limits of the world as most people conceive it.

Like Nietzsche and Dostoevsky, Wittgenstein saw beyond the cultural moment, but unlike them, he didn’t catch the wind of the currents that would shape the next century. Instead, he navigated what lies inside and outside the conceptual frame—clearly demarcating the boundary between what can be signified with language and what transcends it.

This he did at around 30, writing the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Believing he had said all that could be said in a masterful series of self-evident, yet enigmatic propositions, he concluded the treatise by marking the line between here and eternity:

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

At the time, Wittgenstein saw this as a monumental accomplishment, the perfection and genius that would finally ease his mind, secure his intellectual status, and give meaning to his life. Yet, little did he know, this was merely a single stop on his journey. Soon, he would realize that he had constructed a static, homogeneous world—one that left no room for change or disparity, a world unable to articulate the fullness of experience, let alone what lies beyond it.

Formative Years and Influences

Wittgenstein was born into one of the wealthiest families in Europe at the fin de siècle. The Wittgensteins were not only industrial magnates but also prominent socialites. Karl Wittgenstein, Ludwig’s father, was a towering figure in Austrian industry, making the family among the richest in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Their social circle included notable figures, and they hosted cultural events featuring performances by artists like Johannes Brahms.

Despite their affluence and social prominence, the Wittgenstein family’s life was marked by competitive relationships and emotional turmoil. Wittgenstein’s father demanded that his sons achieve the same stature he had reached. For all in the family, it seemed it was "genius or death." By the time Wittgenstein had reached his 20’s, two of his brothers had already committed suicide, and eventually, four of the eight siblings would meet the same fate. This traumatic backdrop left a lasting imprint on Wittgenstein's worldview, intensifying the pressure to carve out his own path. His family’s towering legacy became intertwined with his own existential battle: to reach perfection and genius, or to fall into the same despair as his brothers.

Act I: The Wartime Experience and the Tractatus

Wittgenstein's religious belief began to take shape during his service in the Austrian army in World War I. His wartime experiences, intertwined with his reading of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, became a spiritual crucible, driving him to confront the fragility of life and the chaotic randomness of death. The brutality of trench warfare, combined with the personal trauma of losing his third sibling to suicide, forced Wittgenstein into a deep confrontation with the meaning of existence.

It was around this time that he wrote in his journal:

Perhaps the nearness of death will bring me the light of life. May God enlighten me. I am a worm, but through God, I become a man. God be with me. Amen.

This was more than a cry for survival—it was a desperate plea for something transcendent, a light that could bring order to the turmoil within and around him. Wittgenstein saw his search for meaning as a matter of life or death. He felt compelled to achieve perfection and intellectual genius or risk succumbing to the despair that had claimed his siblings.

The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus became his response to this inner turmoil—a work that sought to impose order by defining the limits of thought and language. Through it, Wittgenstein aimed to create a framework that would give meaning to his life by distinguishing what could be expressed from what lay beyond language.

Yet, despite its precision, the Tractatus ultimately fell short. Its logical structure illuminated not the essence of life but the vastness of what remained unsayable—love, faith, death. Wittgenstein had indeed proven his genius, at least to others, but intellectual recognition provided no lasting peace. If anything, his success only clarified that he had not found what he was truly seeking.

Act II: Embracing Spiritual Exercises

Disillusioned by academic and intellectual life, Wittgenstein soon left academia altogether, turning instead toward simplicity and contemplative labor. He spent several years as a gardener at a monastery, even applying at one point to become a monk. However, certain doctrinal elements—particularly the Baroque Thomism prevalent in pre-Vatican I Catholicism—prevented him from fully committing to monastic life.

Nevertheless, his time at the monastery profoundly shaped his spiritual outlook. Wittgenstein began to embrace what philosopher Pierre Hadot called "spiritual exercises"—practices aimed at transforming the self rather than acquiring theoretical knowledge. These exercises, such as confession, silence, and repentance, allowed him to confront his inner struggles more directly.

One significant spiritual exercise was Wittgenstein’s act of making amends. Years after harshly disciplining children during his time as a schoolteacher, he returned to apologize to those he had wronged. This act of humility and repentance mirrored the Christian practice of confession, reflecting his growing belief that true transformation came not through intellectual achievement, but through moral and spiritual growth.

Silence became equally central to his spiritual practice. For Wittgenstein, it was not merely a retreat from worldly noise but an active engagement with the limits of language itself. In silence, he confronted the ineffable aspects of existence—those things beyond logic or words—and through this, he found a sense of peace. It deepened his apophatic approach to life, where embracing the unknown took precedence over mastering concepts.

Act III: The Spiritual Turn and Final Reflections

Wittgenstein’s spiritual exercises profoundly influenced his later work, especially in Philosophical Investigations, where he moved beyond the rigid logical frameworks of the Tractatus. No longer was he concerned with establishing propositional truths; instead, he shifted to an understanding of meaning as something lived and experienced, shaped by one’s form of life and manner of engaging with the world.

This philosophical evolution mirrored his spiritual one. Wittgenstein increasingly embraced an apophatic stance, recognizing that the most important truths—about God, love, and death—could not be captured by language. Instead, they could only be approached through humility and surrender. His later work reflected this apophatic sensibility, as he became more concerned with the limitations of language and the importance of silence in acknowledging the mystery of existence. The unsayable, which was a boundary in the Tractatus, had now become an invitation to live within that mystery, rather than to explain it.

In 1947, Wittgenstein wrote, "I have had a letter from an old friend in Austria, a priest. In it he says that he hopes my work will go well, if it should be God's will. Now that is all I want: if it should be God's will." This remark encapsulates Wittgenstein's growing acceptance of divine providence, marking a shift from the need to control and define to a willingness to yield to something greater. This attitude echoed the apophatic approach he had come to embody—surrendering to the limits of human knowledge and embracing what lay beyond.

His friend Norman Malcolm remarked, "Wittgenstein's mature life was strongly marked by religious thought and feeling. I am inclined to think that he was more deeply religious than are many people who correctly regard themselves as religious believers."

As he faced death from cancer, this acceptance deepened. The tension between his intellectual ambitions and spiritual yearnings seemed to resolve. His last words, "Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life!", were not words of triumph over philosophical complexities but a quiet acceptance of life’s mysteries. The connection between his 1947 letter and these final words is unmistakable: both reflect a profound surrender to God’s will, to life as it is, and to the unspeakable truths that shape human existence. After years of struggling, questioning, and seeking, Wittgenstein found peace not through intellectual mastery, but through this surrender.

He had come to understand that faith, like philosophy, was not something to be conquered, but lived. His spiritual exercises—silence, repentance, and his willingness to embrace the ineffable—allowed him to transcend the limits of thought and live within the mystery of the unknown. In the end, his life became a testament to the transformative power of spiritual surrender. Peace, for Wittgenstein, was not in solving the mysteries of life but in learning to accept them:

What inclines even me to believe in Christ’s Resurrection? It is as though I play with the thought. -- If he did not rise from the dead, then he decomposed in the grave like any other man. He is dead and decomposed. In that case he is a teacher like any other and can no longer help; and once more we are orphaned and alone. So we have to content ourselves with wisdom and speculation. We are in a sort of hell where we can do nothing but dream, roofed in, as it were, and cut off from heaven. But if I am to be REALLY saved, -- what I need is certainty -- not wisdom, dreams or speculation -- and this certainty is faith. And faith is faith in what is needed by my heart, my soul, not my speculative intelligence. For it is my soul with its passions, as it were with its flesh and blood, that has to be saved, not my abstract mind. Perhaps we can say: Only love can believe the Resurrection (Culture and Value).

This morning, the second Sunday after Pentecost, our first reading in the Revised Common Lectionary (Proper 7, Year C) is from 1 Kings 19—the famous passage where Elijah stands on the mountaintop in the midst of a mighty storm, an earthquake, and a raging fire—yet only experiences God after all these deeds of power pass and he hears "a sound of sheer silence" (or "a still, small voice", depending on your translation).

As it happens, a priest friend of mine is taking two weeks off, and so I am "supplying" for her; I will be leading worship at her church this morning, and I am preaching on this reading. So I can only regard your post on Wittgenstein's wrestling with the limits of language and his discovery of God's presence in a silence beyond thought as a serendipitous act of the Spirit!

Here is the penultimate paragraph of that sermon, if you will indulge me:

"So I think when we show up at church, we might want to ask ourselves that question God posed to Elijah on the mountaintop: “what am I doing here?” What am I looking for? What am I expecting? What kind of God do I seek—and is that God who speaks in sheer silence, who suffers on the Cross? And if I discover that I am expecting a God other than the one we find in the quiet, crucified Christ, well, I might need to recalibrate my expectations."

What were his problems with thomism?